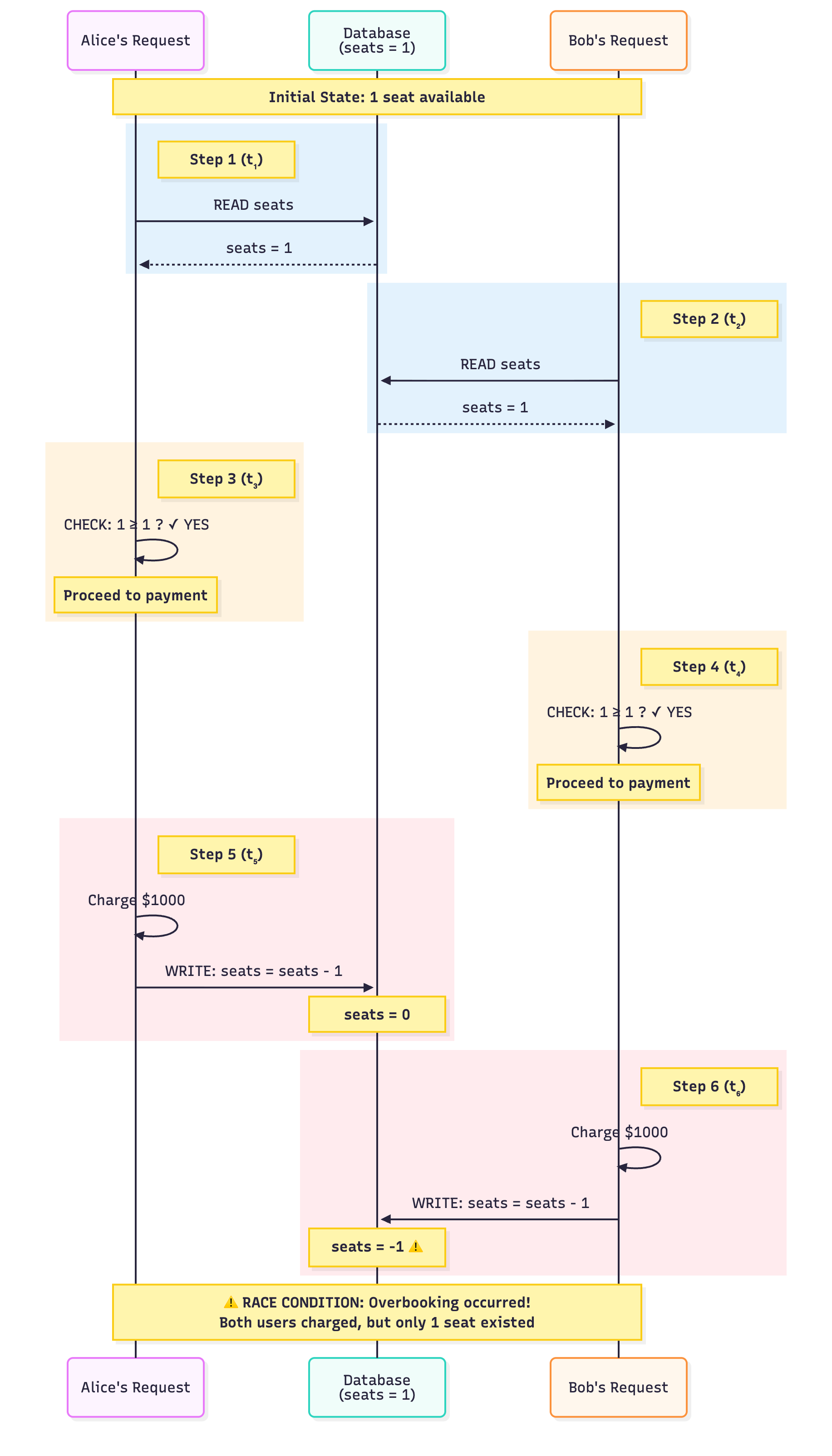

The Problem Statement

When multiple clients, processes, or threads compete for a limited number of resources simultaneously, causing degraded turnaround time and performance, the system enters a state called contention. This is the most common problem in systems that handle high traffic volumes. Without graceful dealing, contention leads to race conditions and an inconsistent state.

Example Scenario

Consider buying flight tickets online. There is only one seat available on the flight. Alice and Bob both want this seat and click “Book Now” at exactly the same time.

Without any coordination, the following events take place.

- Alice’s request reads: 1 seat available.

- Bob’s request reads: 1 seat available (None of the writes have happened yet)

- Alice’s request checks whether 1 ≥ 1 (yes, there is a seat available) and continues to payment.

- Bob’s request checks whether 1 ≥ 1 (yes, there is a seat available) and continues to payment.

- Alice gets charged $1000, and the seat count is decremented to 0.

- Bob gets charged $1000, seat count decremented to -1.

This race condition occurs because reading and writing aren’t atomic. There’s a gap between reading the current state and updating based on it; in that tiny window, many things can go wrong.

The problem can only get worse at scale. With tens of thousands of concurrent users trying to get hold of the same resource, even small race condition windows can cause huge conflicts.

The solution to contention problems varies depending on the nature of the database, whether it is a single-node instance or spread across multiple nodes. In this article, we will look at the solutions assuming our database is hosted on a single node.

Solutions

1. Atomicity

Atomicity guarantees that partial failures are not possible; either all operations in a group succeed or all fail. It solves many contention problems.

ACID-compliant databases ensure atomicity by using transactions. A transaction defines a set of operations as a single unit of work.

For our example, atomicity ensures that flight seat booking and ticket purchase both happen successfully.

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

-- Check and reserve the seat

UPDATE flights

SET available_seats = available_seats - 1

WHERE flight_id = 123;

-- Create the ticket record

INSERT INTO tickets (user_id, flight_id, seat_number, purchase_time)

VALUES ('user123', '123', 'F25', NOW());

COMMIT;If any of these operations fail, the transaction rolls back. You don’t end up with a seat reserved but no ticket issued. But atomicity alone doesn’t solve the problem we saw. Two people can still book the same seat on the same flight.

Here’s why: Alice and Bob can both start their transactions simultaneously, check that available_seats >= 1, and execute their UPDATE statements. Since each transaction is atomic, both succeed, but now we’ve sold two tickets for one seat.

The issue is that transactions provide atomicity within themselves, but don’t prevent concurrent reads of the same data. We need coordination mechanisms to solve this.

Various concurrency control techniques can be used, such as pessimistic concurrency control and optimistic concurrency control. These techniques allow the database to manage concurrent access to shared data in a controlled and consistent manner, helping prevent race conditions. Notice that, basically, we have only two steps when booking a room: read the data and update it. So we can solve race conditions either on a read step or on an update step.

2. Solving Race Condition During Read Step: Pessimistic Concurrency Control

Pessimistic concurrency control is a technique used to prevent race conditions in a database by locking data being accessed or updated. This ensures that only one user can access the data at a time, and that other users must wait until the lock is released before they can access it.

In SQL, pessimistic concurrency control can be implemented using the “SELECT … FOR UPDATE” statement. This statement allows a user to lock the rows of a table that are being accessed and prevents other users from updating or locking those rows until the lock is released.

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

-- Lock the row first to prevent race conditions

SELECT available_seats FROM flights

WHERE flight_id = 123

FOR UPDATE;

-- Now safely update the seat count

UPDATE flights

SET available_seats = available_seats - 1

WHERE flight_id = 123;

-- Create the ticket record

INSERT INTO tickets (user_id, flight_id, seat_number, purchase_time)

VALUES ('user123', 123, 'F25', NOW());

COMMIT;The FOR UPDATE clause acquires an exclusive lock on the flight row before reading. When Alice runs this code, Bob’s identical transaction will block at the SELECT statement until Alice’s transaction completes. This prevents both from seeing the same initial seat count and ensures only one person can check and update at a time.

Performance considerations are really important when using locks. You want to lock as few rows as possible for as short a time as possible. Locking entire tables kills concurrency. Hold locks for seconds instead of milliseconds, and you create bottlenecks. In our example, we’re only locking one specific flight row for a brief period during the booking.

3. Isolation Levels

Instead of explicitly locking rows with FOR UPDATE, you can let the database automatically handle conflicts by raising what’s called the isolation level. Isolation levels control how much concurrent transactions can see of each other’s changes. Think of it as how “isolated” each transaction is from the work of other transactions.

Most databases support four standard isolation levels (these are different options, not a progression):

- READ UNCOMMITTED – Can see uncommitted changes from other transactions

- READ COMMITTED – Can only see committed changes

- REPEATABLE READ – Same data read multiple times within a transaction stays consistent

- SERIALIZABLE – Strongest isolation, transactions appear to run one after another

The defaults of either READ COMMITTED or REPEATABLE READ still allow our flight ticket race condition because both Alice and Bob can read “1 seat available” simultaneously before updating. The SERIALIZABLE isolation level solves this by making transactions appear to run one at a time:

-- Set isolation level for this transaction

BEGIN TRANSACTION ISOLATION LEVEL SERIALIZABLE;

UPDATE flights

SET available_seats = available_seats - 1

WHERE flight_id = 123;

-- Create the ticket record

INSERT INTO tickets (user_id, flight_id, seat_number, purchase_time)

VALUES ('user123', 123, 'F25', NOW());

COMMIT;The tradeoff is that SERIALIZABLE isolation is much more expensive than explicit locks. It requires the database to track all reads and writes to detect potential conflicts, and transaction aborts waste work that must be redone.

4. Solving Race Condition During Write Step: Optimistic Concurrency Control

Optimistic concurrency control, on the other hand, checks for conflicts before committing the changes. If a conflict is detected, the user is notified, and the changes are not applied.

One way to implement optimistic concurrency control in a flight booking system is to use a “version” column in the “flights” table. This column can store a “version number” for each flight, incremented each time it is updated.

BEGIN TRANSACTION;

UPDATE flights

SET available_seats = available_seats - 1, version = version + 1

WHERE flight_id = 123 and version = 1;;

-- Create the ticket record

INSERT INTO tickets (user_id, flight_id, seat_number, purchase_time)

VALUES ('user123', 123, 'F25', NOW());

COMMIT;If these statements are executed concurrently for both Bob and Alice, the first UPDATE statement to be executed will increment the “version” of the flight with ID 123 to 2, and the second UPDATE statement will fail, as the “version” in the WHERE clause is 1 (so zero rows will be updated with the second transaction).

Conclusion

While optimistic concurrency control is a less expensive choice, this approach makes sense when conflicts are rare. In most scenarios, the chance of two people buying the exact same item at the exact same moment is low. The occasional retry is worth avoiding the overhead of pessimistic locking.